It is important to note that these generalities cannot be applied in a perfectly uniform way to all regions of the world. Nevertheless, this introductory article is a first approach to the subject. Let’s start by defining the two terms that make up the title of this article: “Megafauna” and “Pleistocene“.

What does “Pleistocene Megafauna” mean?

Several definitions have been proposed for the term Megafauna . In 1989, PS. Martin proposes to group under this term animals which, when fully grown, exceed a mass of 100 pounds, or around 45 kilograms (abbreviated to kg). However, this definition has since been refined.

Indeed, herbivores tend to be larger than carnivores, as their size provides effective protection against the latter. Consequently, some researchers consider herbivores weighing between 45 and 999 kg to be “large” herbivores, and those weighing over 1 tonne to be “mega” herbivores.

Similarly, carnivores with a body mass of between 21.5 and 99 kg are “large” carnivores, and those with a mass of over 100 kg are considered “mega” carnivores.

The term Pleistocene refers to a geological epoch. This extends from 2.58 million years ago (later abbreviated to Ma) to 11,700 years BC. It thus predates the Holocene, the geological epoch in which we currently find ourselves.

The disappearance of Pleistocene Megafauna

The end of the Pleistocene was marked by a wave of extinctions of large mammals. Reptiles, birds, plants, invertebrates and small rodents were little affected. The same goes for marine animals.

If we look at America, Australia and Eurasia, we see that all mammals weighing over a tonne are disappearing, as are 80% of those weighing over 100 kg. In Europe, we can cite the disappearance of the cave bear around 26,000 / 15,000 BC, or the woolly mammoth around 3,000 BC. In North America, we can cite the disappearance of the giant beaver, Castoroides ohioensis, as well as that of Smilodon fatalis, a felid species, around 9,000 years ago.

Several factors may have contributed to this decline:

- Changes in ecosystem structure due to climate change (the end of the Pleistocene was marked by the transition from an ice age to an interglacial period);

- Increasing scarcity of food resources, due in particular to climatic and environmental variations. Moreover, we must not forget that the disappearance of certain herbivores may have caused the disappearance of certain carnivores that eat them;

- Changes in population structure, particularly from a genetic point of view. Indeed, a reduction in population size leads to a loss of genetic diversity, making species more fragile in the face of environmental change, for example (less ability to “adapt”);

- The expansion of certain species belonging to the Homo genus, leading to overhunting. However, care must be taken, as the predation pressure exerted by human groups can vary according to demographic, geographic and ecological parameters.

These different factors may have played a role in the extinction of the Megafauna. Bear in mind, however, that the reasons for the extinction of these large animals are still debated.

A few examples of species

The aim of this section is not to give you an exhaustive catalog of the Pleistocene Megafauna, but to introduce you to (or rediscover!) some of its members.

Smilodon populator The genus Smilodon was first described in 1841 by P.W. Lund. It was present in South America and became extinct around 10,000 years BC. The size of Smilodon populator is particularly impressive: between 1.8 and 2.3 metres long, with a height at the withers of 1.2 metres. Its body mass was between 220 and 400 kg, making it one of the largest cats ever to have existed. Its canine teeth could measure up to 28 cm in length. Smilodon populator lived in steppe, savannah and even forest environments. It most likely fed on large mammals.

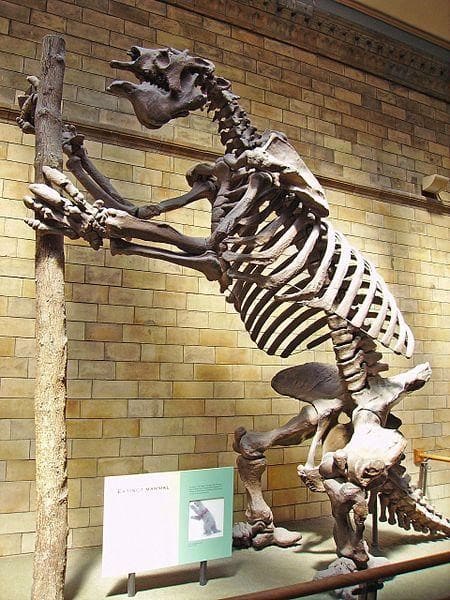

Megatherium americanum This fossil species was discovered in 1788 in Lujiin, Argentina. Living mainly in South America, individuals weighed around 4 tons, making this the largest species of sloth ever to have existed. Megatherium americanum was adapted to temperate, arid and semi-arid climates. This animal was herbivorous, consuming food of varying degrees of hardness.

Procoptodon goliah Procoptodon goliah, the largest kangaroo in the world, would have measured just over 2 meters in height and was probably 1.5 times heavier than today’s red kangaroo. It could be found in semi-arid climatic zones, such as sand dunes. However, specimens have also been found in mosaic landscapes ranging from savannah to sclerophyllous forest. This species fed on fairly tough leaves and stems, and was found on the Australian continent.

Coelodonta antiquitatis : Known as the woolly rhinoceros, this species was present in Eurasia. The individuals measured between 3.5 and 4 metres in length, with a height at the withers of between 1.6 and 2 metres. The total weight of a specimen must have been around 3 tons, and its fur was 15 cm thick to protect it from the cold. He was exclusively vegetarian and lived in the cold steppes, among grasses and herbs. This species of rhinoceros is unusual in that it has two horns!

Megalocerus giganteus: This large cervid could reach 2.10 m at the withers, with antlers extending to 3.60 m. It was present from Ireland to Siberia. The immense size of the woods probably made it impossible for him to live and move around in a dense forest environment. It lived in an open environment with wooded areas, like the great plains of Eurasia.

We hope you found this article interesting. Feel free to ask us questions and give us feedback on the blog. You can also contact us by e-mail. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and TikTok!

We would like to thank Stéphane Péan, archaeozoologist, for proofreading the first version of this article. Any remaining errors or inaccuracies are our fault.

See you soon,

The Prehistory Travel team.

Bibliography :

Anon (n. d.) – Amazon.fr – The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives – An Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History – Anton, Mauricio – Books, https://www.amazon.fr/Big-Cats-Their-Fossil-Relatives/dp/0231102291 [Accédé le 29 mars 2023].

Anon (2017) – Quaternary Extinctions, UAPress. https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/quaternary-extinctions [Accédé le 29 mars 2023].

Bargo M.S. (2001) – The ground sloth Megatherium americanum: skull shape, bite forces, and diet, Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 46, 2.

Boeskorov G.G. (2012) – Some specific morphological and ecological features of the fossil woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach 1799), Biology Bulletin, 39, 8, p. 692-707.

Fortin Corinne, Guillot Gérard, Le Louarn Bonnet Marie Laure, Lecointre Guillaume (2009) – Guide critique de l’évolution, Edition BELIN.

Lister A.M., Edwards C.J., Nock D. a. W., Bunce M., van Pijlen I.A., Bradley D.G., Thomas M.G., Barnes I. (2005) – The phylogenetic position of the ‘giant deer’ Megaloceros giganteus, Nature, 438, 7069, pp. 850-853.

Malhi Y., Doughty C.E., Galetti M., Smith F.A., Svenning J.-C., Terborgh J.W. (2016) – Megafauna and ecosystem function from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 4, pp. 838-846.

News O.H. 10am-5pm M.-S. 10am-9pm W.C.C.D.A. 1 W.S.S.N. 2010 A.P. +61 2 9320 6000 www australian museum C.© 2023 T.A.M.A. 85 407 224 698 V.M. (n. d.) – Procoptodon goliah, The Australian Museum. https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/procoptodon-goliah/australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/procoptodon-goliah/ [Accédé le 29 mars 2023].

Stuart A.J., Kosintsev P.A., Higham T.F.G., Lister A.M. (2004) – Pleistocene to Holocene extinction dynamics in giant deer and woolly mammoth, Nature, 431, 7009, p. 684-689.

Stuart A. (2004) – The extinction of large mammals, Pourlascience.fr. https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/paleontologie/https:https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/paleontologie/l-extinction-des-grands-mammiferes-5469.php [Accédé le 4 décembre 2023].

Werdelin L., McDonald H.G., Shaw C.A. (2018) -Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth, JHU Press, 241 p.