What is a primate? When did these first appear?

The primate order

Primates are an order within the mammal class and the animal kingdom. This order was created in 1758 by Linné in the 10th edition of his Systema naturae.

As mammals, primates are iteroparous, meaning they can reproduce several times during their lifetime. Primates also have a specific growth pattern that stops once they reach sexual maturity. Like mammals, primates are a senescent species. Individual mortality rates increase with age. Finally, mammals are animals with chromosomal sex determination.

The order Primates includes over 500 species of primates, divided into 12 or 13 families. Primates are found all over the world, but with the exception ofHomo sapiens, Macaca sylvanus in Gibraltar and Macaca fuscata in Japan, they are restricted to tropical and subtropical zones, in forest environments or environments with both savannahs and steppes. Primate species are extremely diverse. Some are diurnal, while others are nocturnal. The smallest primate species weighs 30 grams (Madagascar microcebe), while gorillas can weigh up to 250 kilograms. Most primates are arboreal, although some species, such as macaques, are semi-terrestrial. The definition and classification of primates still raises questions due to the great morphological diversity within this order.

What are the characteristics of primates?

Primates share many common characteristics. Here are just a few examples:

- The volume of the olfactory organs is smaller than the cranial volume

- The orbits are positioned on the front of the face, enabling stereoscopic vision, i.e. 3D vision.

- An upright posture of the trunk in the seated position, which frees up the hands

- Feet have opposable thumbs (with the exception ofHomo sapiens , whose big toe is aligned with the rest of the foot, but this is the product of recent evolution).

- Five fingers on each hand

- At least the first finger has a flat nail instead of a claw

- Absence of a third incisor: 2 incisors per hemi-mandible

- A brain that is relatively larger than the body’s proportions

Nevertheless, the various subdivisions within the primates each have their own morphological characteristics.

When did they appear?

The first true primates, called Euprimates, appeared, according to our current knowledge, around 55 million years ago (later abbreviated to Ma). These Euprimates are classified into two groups: Adapiformes and Omomyiformes. Their geographical origin is a matter of debate. Nevertheless, fossil species have been found in North America, Eurasia and on the Arab-African continent.

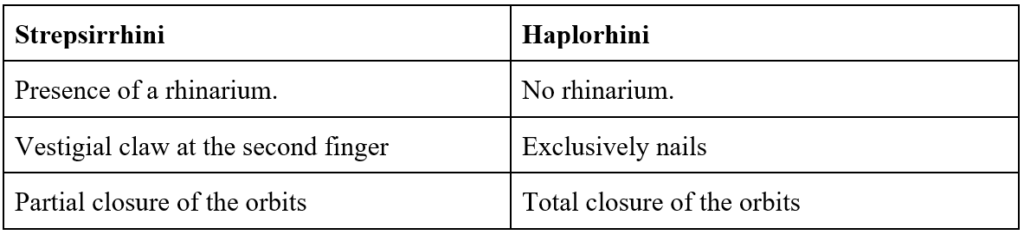

These primates are classified into two suborders: Strepsirrhiniens and Haplorhiniens. The Adapiformes share a number of derived characters with the Strepsirrhiniens, enabling them to be grouped together in this clade. The relationship of the Omomyiformes to the Haplorhiniens is less clear, as they do not possess the characters derived from the latter. This difference in classification is based on the structure of these primates’ faces. If we disregard the fossil groups (Adapiformes and Omomyiformes), here are some features to understand the Strepsirrhiniens and Haplorhiniens dichotomy.

Institute of Human Paleontology

Most Euprimata species disappeared around 34 Ma at the time of a major climatic crisis known as the “Great Divide”. This crisis was survived by the Simiiformes, the first apes proper, which appeared during the Eocene either alongside the Adapiformes and Omomyiformes, or as offspring of one or the other.

Around 33 Ma, the Simiiformes split into two new groups: the Platyrrhines and the Catarrhines. Platyrrhines, nicknamed “New World monkeys”, are exclusively American. They have a prehensile tail and 36 teeth (3 premolars per hemi-mandible). “Platyrrhinian” means “flat-nosed” and, indeed, these monkeys have the peculiarity of their nostrils being spread apart and facing outwards. Catarrhinians, also known as “Old World monkeys”, have nostrils that are close together and point downwards. Their dentition consists of 32 teeth (2 premolars per hemi-mandible). A new subdivision within the Catarrhinians occurred around 24-20 Ma. This division separates the Cercopithecoidea and Hominoidea. The former correspond, for example, to macaques or baboons and are characterized by pronogrady, i.e. a tilted trunk. In contrast, the Hominoidea, to which Homo sapiens belongs, are orthograde, i.e. their trunks are upright. The Hominoidea group includes Man and his closest relatives, the chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla, orangutan, gibbon and siamang. These species are divided into the following families: Hylobatidae, Pongidae and Hominidae(Homo sapiens).

As you can see, Homo sapiens is a primate and an ape like any other! Homo sapiens is the only primate species without an opposable thumb on its foot! We hope you now know each other a little better!

Feel free to ask us questions and give us feedback on the blog. You can also contact us by e-mail. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, LinkedIn and Twitter!

See you soon,

The Prehistory Travel team.

Bibliography :

[1] Dominique Grimaud-Hervé et al., Histoire d’ancêtres. La grande aventure de la Préhistoire, Errances, 5e édition, 2015.

[2] C. F. Ross, R.D Martin, “The role of vision in the Origin and Evolution of Primates, In book: Evolution of Nervous Systems, Publisher: Academic Press, 2007.

[3] Chris Springer, Peter Andrews, The complete world of Human Evolution, Thames & Hudson Ltd Revised edition, 2011.