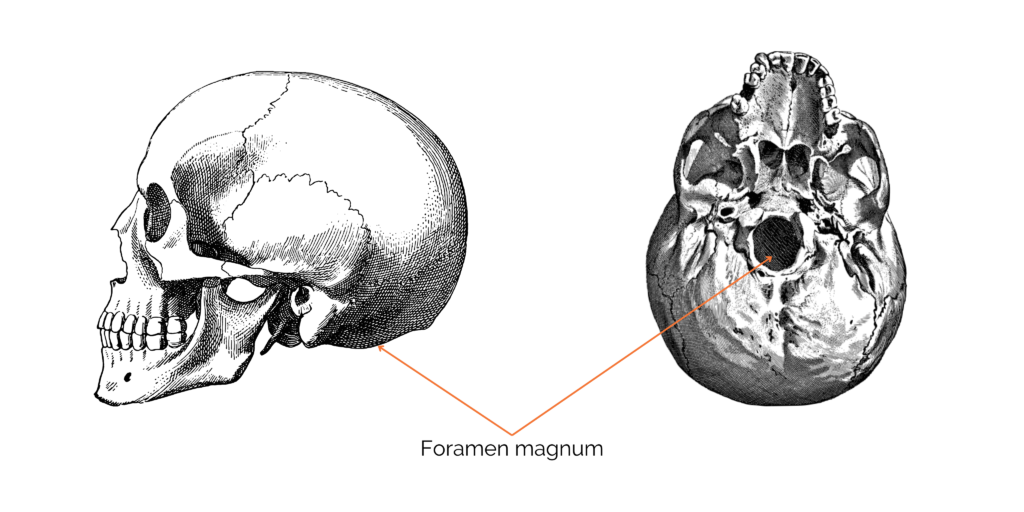

Skeletal adaptations in the skull

In Homo sapiens, the head rests on top of the spinal column via the foramen magnum. The foramen magnum, positioned under the skull, allows the spinal column to be attached and the medulla oblongata to pass through. The medulla oblongata forms the lower part of the brain stem. Its position under the skull is very important, as it gives indications of the general position of the body and therefore of the mode of locomotion. In our species, the foramen magnum is located in the center of the skull and is oriented upwards and forwards, enabling us to keep our heads upright during bipedalism. In other primates, the foramen magnum is in a more posterior position, pointing downwards.

Skeletal adaptations in the spine

The spine of Homo sapiens has a quadruple curvature: sacral kyphosis, cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. In non-human primates, the spine has a curvature. In the chimpanzee(Pan troglodytes), for example, cervical lordosis is less pronounced, and there is only a single curvature for the rest of the spine. This specificity in today’s human beings allows for greater muscular efficiency in maintaining the body upright. This also provides greater resistance during bipedal gait.

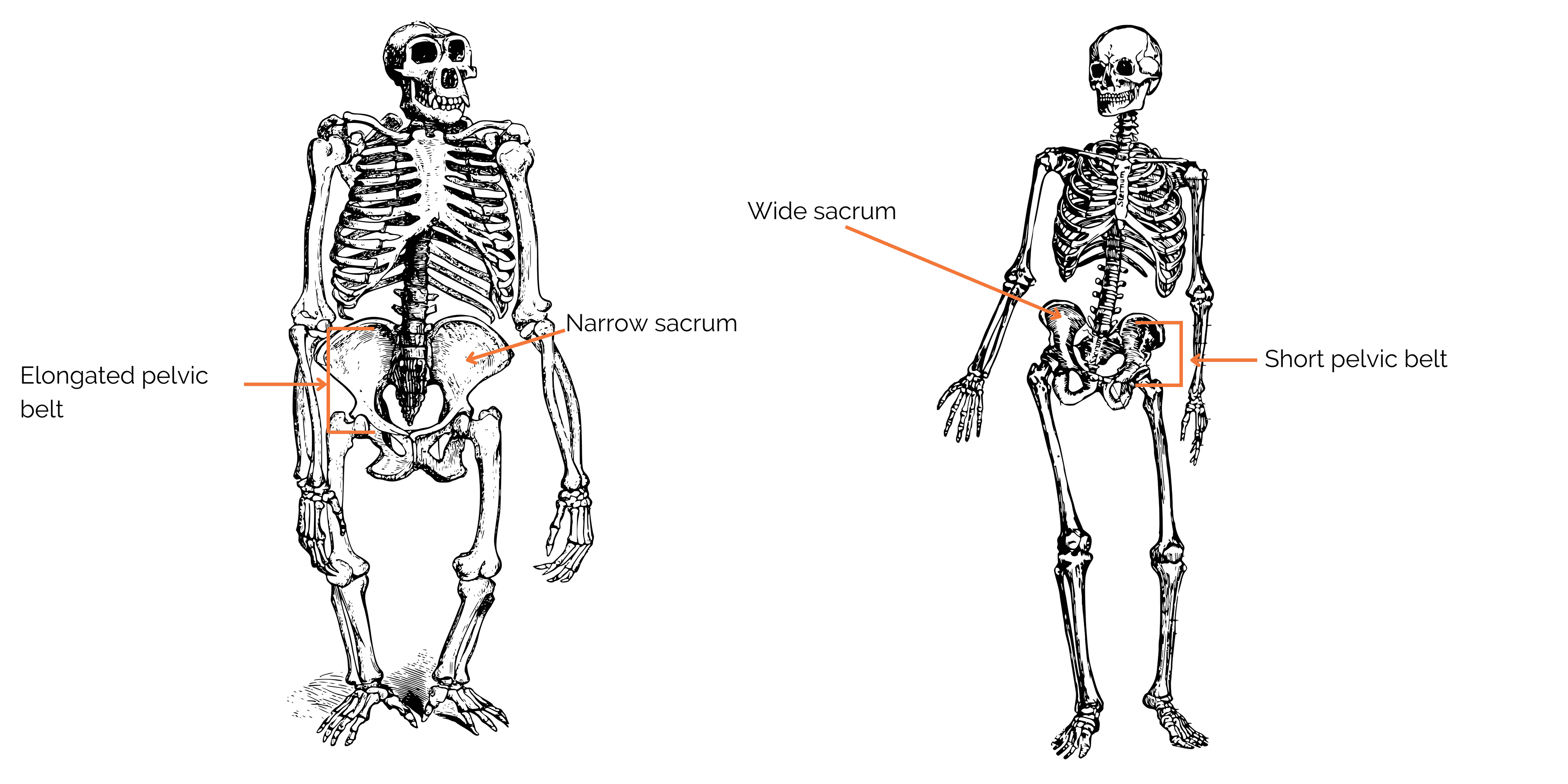

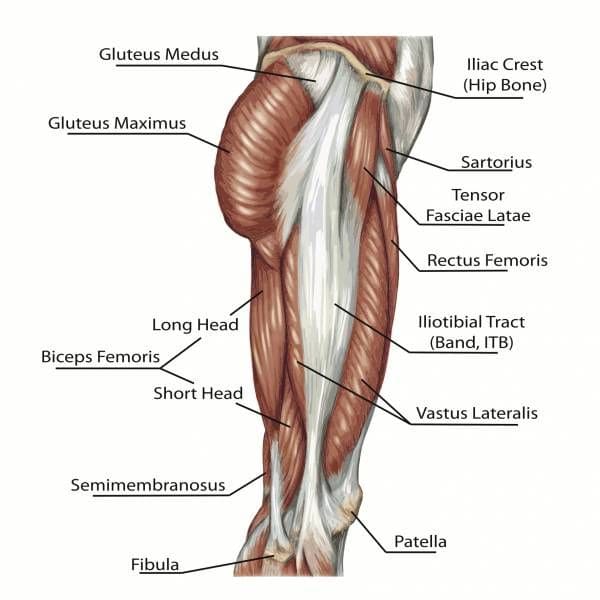

Skeletal adaptations in the pelvis

In non-human primates, the pelvis is very elongated. In human beings, the acquisition of bipedalism has been accompanied by a widening and shortening of the pelvis (known as compression). This remodeling offers numerous biomechanical advantages, such as visceral support. This enables optimal positioning of the gluteus medius muscle (formerly gluteus medius), which becomes a thigh abductor rather than a rotator as in other primates. This limits trunk oscillations in the frontal plane (to the sides), compared with the bipedal, shuffling gait of chimpanzees. On the other hand, in the sagittal plane (direction of travel), our center of mass oscillates, allowing us to recuperate our energy and thus have a very efficient bipedal gait!

The ischial tuberosities have also migrated posteriorly in humans, providing the hamstrings with optimum leverage for the erect bipedal posture. What’s more, the lumbar spine and pelvis serve as anchors for the trunk muscles, keeping the trunk optimally erect and requiring little muscular effort.

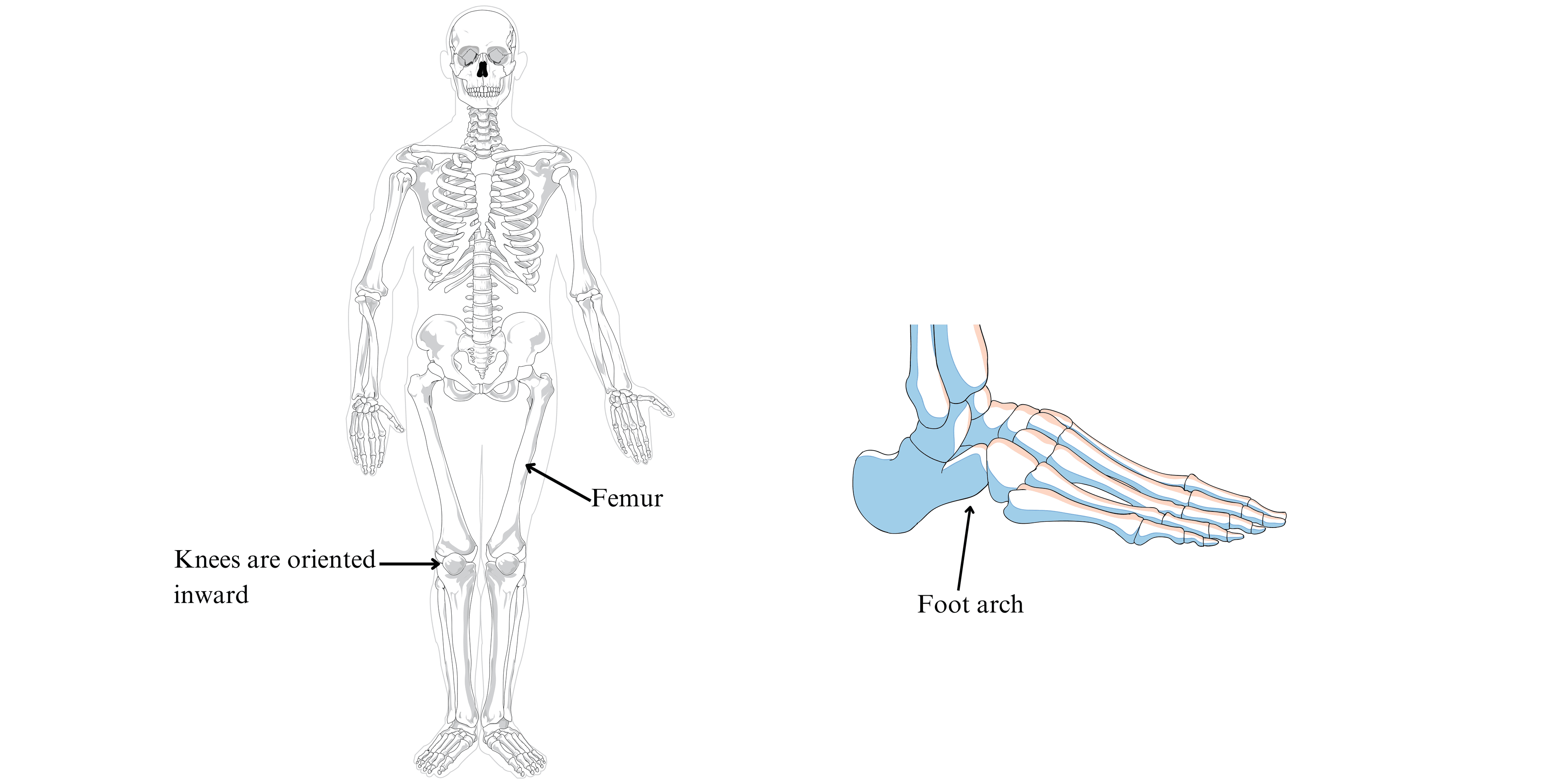

Skeletal adaptations in the lower limbs

With bipedalism, the lower limbs must carry the entire weight of the body. These limbs are longer in H. sapiens than in other primates. In addition, the femurs are oblique and the knees inward, bringing them closer to the body’s line of gravity. Knee and ankle joints are reinforced for greater stability. The joints of the lower limbs function mainly in the parasagittal plane (direction of gait).

The foot is hollowed out by two arches, one transverse and the other longitudinal, stabilizing the foot on the ground and transferring weight from the heel to the forefoot. The big toe is aligned with the other toes, which, among primates, is unique to our species! The toes are short and the heel is massive.

Here are a few examples of the musculoskeletal adaptations needed to enable us to walk upright efficiently for long periods. Bipedalism is at the heart of the debate on the emergence of the human lineage. Indeed, this is considered one of the main criteria for determining whether an extinct species whose fossil remains have been found belongs to the Hominins or not.

We hope you found this article interesting. Feel free to ask us questions and give us feedback on the blog. You can also contact us by email. Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok,LinkedIn and YouTube to keep up with all the latest news!

We would like to thank François Druelle, a research fellow specializing in primatology and locomotion, for reviewing the first version of this article.

See you soon,

The Prehistory Travel team.

Bibliography:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2750765/

- https://journals.openedition.org/primatologie/10855

- D. Grimaud-Hervé et al, Histoires d’ancêtres, 2015, éditions errance

- Springer C., Andrews P., The complete world of Human evolution, 2011, ed. Thames & Hudson

- G. Berillon, “Les multiples bipédies des hominidés”, 2005

- Rasmussen et al, “Tarsier-like locomotor specializations in the Oligocene primate Afrotarsius”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, vol. 95, 1998

- https://journals.openedition.org/primatologie/10570

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2053-y

- https://www.geo.fr/histoire/celebre-australopitheque-lucy-avait-des-muscles-massifs-pour-se-tenir-droite-et-grimper-aux-arbres-modelisation-3d-demarche-215161